One of the initial goals of writing about games was to connect tidbits learned from studying psychology with instances of good design. Which is why I figured I would do something different with a post about Paper Mario. What I want to do is look at a concept from social psychology I find particularly valuable and use it as a lens to look at the value of stories and world-building in Paper Mario specifically. Part of this was also inspired by the question of how Paper Mario works within the RPG genre as a kid-friendly iteration of the genre, and by the fact I recently was able to witness two playthroughs of the game nearly simultaneously.

There’s other particularities about this post I want to get to before starting. I aim to begin with an explanation of the psychological concept I wish to explore, which means that I won’t actually get to delve into the game until decently far into the article. The other large particularity is that I’m delving into the sort of territory that is more properly covered by researchers, as I personally don’t actually possess the ability or resources to really research my claims. Which means that, more so than previous posts, this is a highly theoretical opinion I’m writing today. If anyone reading this is interested in research implications and has the tools or resources to obtain the data necessary to delve into this topic properly, I highly encourage you to do so and look forward to the results.

Self-Efficacy and Performance

In order to avoid being a textbook, I’ll keep this as brief as possible. Self-efficacy theory refers to a theory proposed by psychologist Albert Bandura as a way to understand how people behave relative to the outcomes they expect. Simply put, studying reinforcement and learning could not be understood simply as an individual knowing that a specific outcome will result from a specific action, but also as how much that individual finds themselves capable of performing the specific action. By grounding the execution of the behavior in the individual’s perception of themselves, self-efficacy theory allows us to better understand why people might or might not perform a desired action regardless of the rewards it provides. For example, it is not just a matter of having someone understand that they need to study in order to perform well on a test, but also a matter of reasoning whether that particular individual will find themselves capable of properly studying in order to ensure the expected behavior (in this case, performing well on the test.)

There are more layers to this concept, but from this shallow understanding it is easy to see where I am going with this, and how it relates to games. Game design is at a point where we understand very well how to effectively use reinforcement cycles in order to engage players. Whether it is something predatory like a slot machine randomizing an outcome to provoke further instances of an action, or something simpler like a random enemy in an RPG having a small chance to drop the Sword of Kings that will make the player dramatically stronger… learning is something that game designers get.

With all that in mind, I want to go the extra mile by considering self-efficacy and ways in which games not only ensure that the reinforcement cycles are obvious, but also find ways to motivate the player in ways that boost their confidence in their performance. Lots of games are doing this, of course, and it’s the sort of empowering tool that makes me love games as a whole. It’s one of the reasons I cannot stop loving Celeste or Cuphead. But before I keep getting distracted, let me talk about how this emerges in Paper Mario’s interpretation of a child-friendly RPG.

Bringing the Mechanical Approachability of Mario to the RPG Genre

For those unfamiliar, Paper Mario is basically what happens when you ask Nintendo to make an RPG game. Much like Smash did its own thing with fighters and Splatoon had its own way of doing shooters, Paper Mario in 2001 was an instance of Nintendo giving a genre their own take. Developed by Intelligent Systems, Paper Mario wasn’t even the first instance of this, and started out in development as a sequel to Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars. This latter was the first Mario RPG we were graced with, and gave us multiple mechanics that would define every Mario RPG since.

At its core, Paper Mario (and its predecessor) function like every other classic Japanese RPG, by having gameplay split between overworld exploration and turn-based battles. Given the Mario in the title, exploration of the world involves simple platforming, jumping and basic puzzle-solving. Enemies move around this overworld as well, and engaging them in the overworld prompts the beginning of a battle. It is in battle where we get the other Mario-ification of the RPG: the Action Command. Instead of just selecting actions and watching them unfold, most things a player can choose to do will also prompt a specific set of inputs that can boost the effectiveness of the action. In rare cases, failing this action command can even make the attack entirely useless.

Admittedly, at the time of Paper Mario’s release (early 2001 for the west) there was another franchise that had already made RPGs popular for kids, that being Pokemon. Nevertheless, it is nice to look at the ways in which Paper Mario solves issues with the approachability of the genre. The overworld looks colorful, the characters and environments resemble a story book, and the battle system ensures younger players can remain engaged in battle by directly performing actions, as opposed to just waiting for the outcome of their selections. Given the kid-friendly vibe, it comes then as a surprise that Paper Mario is still notably challenging and remains popular with older players as well. In an age where kid- or casual-friendly games are simply just easier or shorter versions of traditional titles, it’s interesting to look back at a title where this was not necessarily the case. And it is here where we begin to go into self-efficacy, and how Paper Mario guides players towards success.

Pacing and Story to Ensure Success

Regardless of how much difficulty Paper Mario provides, seeing it played twice makes it easy to see the core truth of the design. That is, for every challenge the game throws at you, there is always a specific, by-design solution that the game pretty much throws at you. In some cases this comes up right after encountering an obstacle, but more often than not it’s the opposite, with the game giving you a tool for success right before it becomes necessary. For example, after gaining a partner that allows you to completely avoid hits by going invisible, the game follows by having enemy units that can spend a turn charging their attack. The tell is so clear that the game might as well flash a signal telling you to use your new partner to dodge the super-powerful hit.

While this is the case with most games (or at the least, it should be), Paper Mario keeps the solution simple by not requiring extensive searching of it via NPC dialogue or back-tracking. In the scenario mentioned above, for example, Lady Bow (the partner who allows Mario to disappear) must be kept in the player’s single party slot for story-focused events that have you disappear in order to progress. While more experienced players may muck around and change their partners constantly, a casual player just going through the experience is likely to keep these partners around based on story events and, as a result, find themselves with solutions to problems set up prior to encountering obstacles.

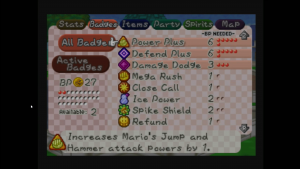

Pretty much every chapter boss in the game works this way too. Lady Bow can disappear? Good thing, because the boss of that chapter has a charge move that, after telegraphed, deals tons of damage. The game just gave you a partner capable of using water? Great thing, because the boss of that area attacks with fire and engulfs itself in flames. What’s more, whenever the game is unable to just shower you with partners to solve problems, it can instead give you badges that will. Badges in this game essentially being equipment that alter specific values or behaviors for Mario, such as increasing damage dealt, granting special moves, etc. A good example of this is the Quake Hammer badge, which allows you to hit your hammer on the ground to make the floor and ceiling shake, being found in the same chapter as the dungeon where enemies start sticking to ceilings to avoid contact (incidentally, this same dungeon also takes place after the player obtains Parakarry as a partner, a flying ally who is also capable of taking these enemies down and who is required to obtain the badge).

What this essentially leads to, behavior-wise, is that a player can feel safe following the golden path of the game while knowing that tools for success will always be at their disposal. While this should be an obvious, core aspect of a properly-designed game, the ability of this game to telegraph this pattern does wonders for establishing a player’s capability to solve any challenge. Where something like Pokemon Red and Blue will have sections that require players to go back and forth between areas before determining that a specific item is necessary to go past a guard, Paper Mario ensures no player is stuck or locked from the experience by keeping those key items and abilities linearly within the golden path.

There’s lots to be said about the pros and cons to this approach and how Paper Mario solves them, but for now I want to stick to how it relates to self-efficacy. By setting up earlier chapters with multiple instances of the player being highly capable relative to their environment, the game is able to set up an expectancy of success. Even if a player does find themselves overwhelmed by high frequency of enemies, they are given tools and abilities to avoid those enemy encounters and are not punished by it thanks to an experience system that changes how much experience Mario gains from an enemy relative to the player’s level. What’s more, the story itself is filled to the brim with interactions that continuously frame the player character, in this case Mario, as a highly capable hero who is constantly solely responsible for solving all issues. As a case for a kid’s game, it is excellent in that all instances of the game addressing the player involve either all-out confidence, or comedic instances of the opposite. The end result is that players are able to maintain confidence about even the harshest of in-story challenges, and spikes in difficulty do not lead to resignation, frustration or learned helplessness.

Failsafes and Diversity of Solutions

I talked briefly above about Paper Mario providing solutions in a linear fashion, and I can see how that presents a weak case for the value of its gameplay in a context where players are more interested in non-linearity. Because of this, I want to bring up the genius in how Paper Mario bridges the needs of a casual RPG experience while still providing excitement for more experienced players.

Like I mentioned before, every challenge in Paper Mario has a telegraphed, game-desired solution. However, along with this the game also provides enough variability with its badges and partners that it is highly possible to solve different challenges by different means. This leads to a game that’s essentially unique in each playthrough and can, hypothetically, make every individual’s experience wildly different much in the same way every player going through Pokemon casually is likely to have a different team composition, and a varying experience as a result. So in Paper Mario, where one player might follow the expected route and defeat enemies with the expected partners and badge combinations, other players may instead equip themselves with wildly different combinations of badges that will grant Mario the ability to ignore these partner-specific solutions. That the game allows you to select which stats to boost upon each level-up further ensures that every player is capable of running wildly different setups that can all lead to success.

Because of this, Paper Mario is able to ensure success for less experienced players while also welcoming those who desire more strenuous challenges. Ideally, this also creates a scenario where a younger player can become familiar with the intended design of the game from experiencing it once, to then revisit the game to consider more complicated scenarios. This was, at least, something I myself was able to do as a child, and I am sure others out there who experienced this game on release and still play it to have done the same.

The other brilliance of the Paper Mario design related to motivation is how aware the game is of moments of expected failure. While it is mostly the case that with proper attention most challenges in the game can be overcome with ease, the game does feature a few optional bosses that are particularly brutal. For most of these, however, the game does ask you multiple times if you are sure about facing them, which is particularly the case with the dreaded Anti Guy (a super strong Shy Guy enemy in Chapter 4 that blocks a treasure chest.) By clearly warning players of particularly difficult enemies, the game avoids instances of unfair deaths that may prompt disengagement as a result, since the game does boot the player back to the title screen upon reaching a game over. While it remains the case that failure against these strong enemies is likely to result in learning, and thus ensure later victory, by protecting players from particularly brutal failure the game ensures that motivation isn’t lost, as lack of motivation might in turn affect a player’s capacity to act properly in their strategy and action commands. Of note is that in this particular instance with the Anti Guy it is also possible to learn his favorite food and avoid confrontation altogether, which is great as it keeps the item it guards from being an exclusive reward.

The Value of Story

Overall, I feel that mechanically a lot of this post rings true with what developers and designers currently do. Many games out there have pacing and teaching down to great precision, and testing allows further of that by letting game makers refine the order and sequence of levels and challenges to ensure maximum enjoyment from players. So to close today’s post, I want to instead harp a bit more on story, since I feel that is one of the aspects that has become more and more lost with time.

In the context of how people play games now compared to before, it’s easy to see why this happens. The current perception of gaming for kids is that everything needs to be easy and that everything needs to be quickly accessible to prevent boredom. Because in a world with thousands upon thousands of other games and media to compete with, it makes sense to not expect a child on their parent’s tablet to want to just sit there reading a tutorial when they could instead, for example, just hammer their fingers on the screen to make things explode and make sounds.

Still, being able to re-experience Paper Mario is a joy in that everyone gets the same expression of happiness and childish wonder when going through it. Story-wise it provides richness in world and character that tends to go ignored now, even by the very Paper Mario franchise this game established. It is empowering to a player to constantly have the context of an entire world at their hands and to be able to see the consequences to their positive actions. Having Toad Town as a hub the player goes back to frequently gives a sense of time progression and importance to the player’s presence, and it becomes easy to sympathize with the goals the game wants one to accomplish when the results grow the world around you and expand what you have access to.

These sorts of locales and characters that the first three Paper Mario games excelled at providing are the sort of storytelling methods that can empower younger players to realize the effect of their actions on others. It’s the sort of storybook only a game can deliver as it maintains the egocentrism of early childhood (by having the world and events revolve around the main character) while still highlighting the importance of doing the right thing and helping others. It is particularly nice to have experienced this sort of thing in a context wherein games are once again blamed for modeling violence, while those critical non-gamers ignore instances like this game of modeling pro-social behavior and developing self-efficacy that can empower kids to deal with other challenges in life.

Stray Notes

- Interestingly, despite having excellent cycles of success and empowerment, Paper Mario starts out with an instance of failure by forcing the player to lose against Bowser. That said, the argument can be made that the fight being scripted prevents the player from drawing any value from that experience other than the realization later in the game of how much they have grown as a player.

- I would recommend people look up Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory paper, as the concept in itself is probably one of the more approachable ideas for game design. The original article itself is pretty dense (and decently long), so if academic literature is not your forte I’d simply suggest looking up videos of it on youtube or perusing the Wikipedia article.

- The localization of this game is fantastic, and as a whole it’s great to know that this high standard remains across the franchise. The comedic take on the Mario RPG formula is a phenomenal choice, and makes the games even more approachable and enjoyable as well.

- I’ve been intentionally avoiding the whole debate over what Paper Mario has become as a franchise. For those curious, I have completely avoided purchasing and playing Sticker Star and Color Splash, for the simple reason that I know they are games that are not made with my interests in mind. Wouldn’t mind playing them for academic research, as a designer and not a gamer, but as long as they cost money I refuse to support them on principle.

- If there’s one thing in this game I failed to understand, it is the presence of so many status conditions that all ultimately do the same. The other thing I don’t like about them is that they possess an unseen probability to fail. The problem with this is that the first time I used one of these items, it failed, and as a result I just never used them again. It would have been interesting to have certain match conditions affect the likelihood of specific status effects in a way visible to the player.

- Other bit I want to praise: the segments in between chapters with Princess Peach where she learns details of Mario’s next adventures. Not only are they adorable and give actual character value to the Princess, they also function as fun and enjoyable transitions from one highly-focused chapter to another.

- Pretty much everything I praise in Paper Mario can be said tenfold for Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door, one of the cases in gaming where the sequel perfectly nails everything great about the original and goes beyond.

- A couple shout-outs to people who helped with this one: First, to one of my readers, who I know as lr-hr-rh, for pointing out multiple resources of gaming research by the University of Michigan. Second, to those who went through this game for my enjoyment: Erik G. , who is still going through this game on my Twitch channel ( twitch.tv/Nephy4 ); And Ben R. Sheldon, who recently completed the game on his own Twitch channel ( twitch.tv/stkildafan ), and has moved on to Super Paper Mario and, soon, Paper Mario: Color Splash. Of course, both channels are worth a follow and a watch (particularly mine, of course!)

- This will be my last post in some time. GDC is coming up and because of that my focus will not be on the blog. Then soon after that I will be going on a vacation. While I may be thinking up post ideas and playing games casually, I don’t expect anything to go up here from this post until near mid-April.