One of the things I find myself easily writing a lot about when it comes to games is the multiple gaming franchises that, for some reason or another, were great during my childhood but have failed to maintain that fun over future iterations. Things like Paper Mario, for example, where the newer installations have completely failed to capture the joy that the first ones did. But as much as I want to write about the Paper Mario series (one day…), today I want to focus instead on another series that a lot gamers from my generation miss: the Mario Party series.

The reason I wish to focus on this one lies in the fact that I’ve noticed a lot of the nostalgic comments and joy towards this game involve, well, unfairness. Multiple people enjoy sharing a recollection of that time someone’s victory was unjustly taken away at the last turn by an item or a mechanic that instead left them with nothing. It’s the sort of thing that, to the victim, can be extremely angering and unjust, but somehow at the end of the day the recollection of it is particularly precious, and people for the most part still want to play these games again.

So why is that? If so much about game design is to balance things to a relatively fair outcome, why is it that everyone clamors for the return of a blatantly unfair game? With that question in mind, we dive into the question of the design choices that make Mario Party such a great party game. I also intend around the end of this post to talk briefly about why the recent iterations of it haven’t met the level of interest that the earlier titles captured so easily.

Skill, Strategy and the Illusion of Control

Let’s start by dissecting the mechanics of Mario Party. At its core, the game consists of a board game where all players start at the same spot and roll a die to move around the board. The goal is to be the player with the most stars at the end of the game, and to get stars players have to collect coins and be the first to make it to the place on the board where an NPC will sell you a star for twenty coins. Turn order itself is also defined by dice rolls, so ultimately, disregarding everything else, the question of who makes it to the star first is entirely chance. This portion of the game is as deep as Candyland.

Then there are the mechanics that begin adding elements of choice. Boards in general all have gimmicks, branching paths and other mechanics that mean players can diversify their approach to the star. Where someone could aim towards making it there via the fastest path possible, someone else could, instead of starting a losing race, go down a different path to pursue items, coins, or events that will change the conditions of the board. This diversification is further encouraged by the mechanic of spaces with different effects, so that a player is likely to take a path with blue spaces (which grant coins) more than a path that will land them on a red space (which takes away coins). There are also green spaces that can have random effects; some positive, some negative, and some that are just simply chaotic.

The coins are what further bring in choice and control. Making a bee-line to the star will not work if the player who gets there first fails to collect 20 coins, and given that landing on blue spaces only grants three coins, the main way to realistically and safely get to that number is to win mini-games. Which is, to me, the brilliant mechanic of Mario Party that ties it all together. Once every turn ends, the game sends all four players to a specific, randomly selected mini-game. These mini-games are, for the most part, skill-based challenges that test reflexes, button-mashing speed, timing, movement and all sorts of different things. Winner (or winners) of the mini-game receive ten coins, and with that the possibility of affording a star.

I could spend all day talking about the specific mini-games and their design, but they are not the current aim of this post. Nevertheless, they are important to bring up in that it’s the core mechanic of Mario Party that maintains engagement and, more importantly, celebrates skill in what otherwise is mostly a game of chance. Of course, there ARE mini-games that are entirely luck-based, and there are also coin mini-games where every player can get coins, but these are so infrequent that it is entirely possible for players who value skill to rely on being able to win mini-games as a path to victory. What’s more, where the stage rewards the player who gets to the star in between all the chaos, the game still rewards ability in mini-games by awarding a star at the end to the player who won the most games, as well as the player with the most coins. Which is ultimately going to be the core praise of Mario Party:

There is, technically speaking at least, a strategy to Mario Party. With the mini-games, you add an element that a player can feel control over to a certain degree, and even if luck does actually destroy the day of an experienced player, they can still remain engaged during the whole experience as a result of knowing that they can enjoy mini-games and probably get rewarded for it. It’s a case for game design that gives control to the player, even if it actually doesn’t given that, at any moment, a random set of events can destroy someone’s perfect game. Meanwhile, the players who do not have confidence in mini-games or lack the experience of their peers still get to remain engaged because of the random element of the game. Let’s focus on that now.

Making Chaos and Unfairness Engaging

Nintendo games are excellent examples of how to design games that can grab multiple ages, demographics, and skill levels. The key to this is the fact that all of their games contain elements that favor lower-skill players at the expense of high-skilled ones. In Mario Party, this manifests in the fact that the game favors end-game upsets, is friendly to king-making, and ensures that all players remain engaged during the entire match.

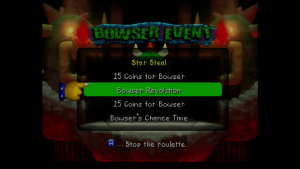

While talking about the game mechanics, I omitted what the game does with Bowser spaces, Chance spaces and with the last five turns of a match. The Bowser space in a level is essentially the ultimate unlucky spot to land on, and while it differs in each game, its role is usually to either disrupt your game by taking away coins or even stars, or to disrupt everyone’s game by redistributing the wealth. Chance spaces, meanwhile, disrupt by randomly redistributing coins or stars between players. Because that’s not wild enough, when the game reaches the last five turns it starts a cut-scene that reminds players of the current standings and then increases coin rewards (and punishments) from the spaces and, varying by game, upsets the board in one way or another. Things like duel mini-games happening if players land on the same spot, or, my personal favorite, turning every red space on the board into a Bowser Space. All of these, particularly the last five turns event, are what really define Mario Party as an evil, unjust game because a player with a solid lead could easily lose the entire game, randomly, right before the end.

What I particularly appreciate also about the last five turns event is the simplicity of reminding players who the winner is, while also (depending on the title) berating other players or the losing player. Here’s where we talk about how king-making defines this game. To be clear, king-making refers to the practice in multiplayer games wherein non-winning players can gang up on the current winner or behave in another such manner that will result in them deciding who the winner is. It’s a practice that allows players who have no chance of winning to retain the element of control by plotting and still manipulating the outcome of the match.

King-making in Mario Party can be particularly beautiful too, and the game offers multiple opportunities to do so. From maps where you can block or alter paths to keep others from movement, to mini-games where you can easily have non-winning players sabotage a winning player from winning. Items in particular are consistent weapons for this, since they constantly feature the ability to have one player steal stars or coins from another, the ability to prompt duels, and other tools like items that switch the positions of players.

The result of these elements is that all players can have an impact on the game at all times. Even a poor player in fourth place with no coins or stars could easily disrupt a mini-game or land on a Chance Time space, completely changing the game even if it is not to their benefit. The ability to maintain all players involved during the experience means that all players are likely to be invested in the possibility of playing this game, in contrast with other board games such as Monopoly where it is usually only the winning players that have fun while the players that lose lack any involvement.

What also cannot be understated is the ability this game has to create memorable moments. In the drive to design balanced and functional games, one of the things designers often forget is the fact that chaos and unpredictable situations can lead to fun and memorable moments for gamers. Even in highly competitive games, where everyone prizes skill and pride, small moments of a technical malfunction or a bug or a disconnect or any sort of unexpected hiccup can make something particularly amusing. It’s entertaining to watch how even competitive players react to glitches:

So even when the worst possible thing happens in Mario Party, even when a player loses all of their effort and work in the last turn, the schadenfreude of the moment and the fact that RNG aligns in order to make it possible is ultimately memorable ad highly comedic in timing, and even the victims of such occurrences will still have that one story to tell later on about that one time where “that !@#$ game” roasted them by taking victory from their grasp. That Mario Party titles, particularly the early iterations, were able to establish a set of mechanics and circumstances that would enable this sort of chaos to develop while still retaining fun and engagement is a credit to the developers at that time, Hudson Soft.

Missing a Franchise That’s Still Around

When creating the title for this post and writing the line “Why do we miss Mario Party?”, what came to mind wasn’t only the fact that it’s strange that most of us miss an unfair, chaotic game. The other layer to the question lies in that Mario Party is for all intents and purposes still very alive, with the latest game in the series having only released last year as of writing (Mario Party: The Top 100 for the Nintendo 3DS). So why are we missing an experience that should still remain?

The easy answer is, of course, nostalgia. Most of us treasure the Mario Parties we experienced in the best circumstances possible, whether that was as a kid with friends sitting around a TV during a sleepover, or in college with various roommates and friends and a couple of drinks. In this sense, missing Mario Party is not so much missing Mario Party as it is missing those particular moments when one was able to engage in a game with friends easily, something a lot of us know as adults is not necessarily as likely to occur or as easy to arrange. With situations like this it’s easy to understand the drive to make every multiplayer experience online, since it’s on the internet where players are capable of finding people at the right time for a match or a game.

But the easy answer is also the boring answer and not the one I’m here to really talk about. The answer I like to think about is the fact that recent Mario Parties, in one way or another, have simply not been able to re-capture the essence of earlier ones.

First of all, there’s the handful of portable Mario Party experiences we have received, particularly on the 3DS which now boasts three Mario Party titles. The success of Mario Party games depends entirely on the availability of multiple players, as it is in that context that all the hilarity of upsets and chaos really gains value. Watching CPU players cause upsets through items and randomization just leads to a feeling of the CPU being stacked against the player, even if it really is just a CPU provoking the same RNG mishaps an actual player would have. This is one of those things where I wager Nintendo accounted for the highly densely-populated cities of Japan as a market, a place where multiple people can be assumed to have a 3DS available, as opposed to the reality almost everywhere else in the world where 3DS users are more likely to be highly scattered and unlikely to cross one another outside of video game-specific events such as conventions and tournaments. Even down to the matter of all players looking at their own isolated screens as opposed to all sharing the same board and focus… ultimately, Mario Party is an experience I would not consider portable friendly, outside of course of the Switch given that it’s a portable console that encourages one-screen local multiplayer.

The other elephant in the room is the Car mechanic that has been present in the past couple of Mario Parties. Instead of having boards that all players traverse individually, all players are placed on top of a car that goes through a stage. Where the previous game involves turns, this one instead ends when the car reaches a specific point. The thinking, I surmise, was that now you could ensure that all players pay attention to each other’s turns given that everyone shares the same fate, and that way you solve the question of how to have players not be bored when it’s not their turn. It’s admittedly a reasonable question as I could see a lot of the earlier Mario Parties suffering from that, since it can be boring to just sit idly while you watch three other players look at the map before deciding where to go. ND Cube, the current Mario Party developers, would later try to solve this issue by having all players move independently in the 3DS game Star Rush, which is why I’m confident this is the problem they meant to tackle all along.

However, in trying to solve this problem I believe a lot of what made Mario Party work originally was undone. Part of the joy in board games is when there’s diversification in how to reach a goal, and independence is of great importance in establishing that diversity. If you tell all players that they share the same fate, what you create is a single path towards victory, something that removes a significant portion of strategy from the equation. Sure, the player driving the car will have agency in which path he takes in a fork, and thus ensure the next player is likely to hit a red space or a negative block. But in the end all players are just on a rollercoaster ride hoping to be the one who happens to be driving when stars can be collected. While earlier Mario Parties were of course also a matter of chance in their movement, each player was independently in control of what goal to shoot for, whether it was to hoard coins and hope to steal a star, or straightforwardly follow the star space as it re-spawns from place to place.

The sad question remains whether the next game in the series will look back at what made the original games great and capitalize on it, instead of aiming to re-make the formula yet again while missing key elements of what made it great originally. A lot of people are hoping that a title like Mario Party: the Top 100 demonstrates a desire from Nintendo to go back to what made the series good, but personally I am still apprehensive as to me it demonstrates a developer that is highly focused on one half of the equation, the mini-games, while still remaining clueless as to what made the whole package mesh together. And to really get there I think it is necessary to remove the cap of designer for a second and instead jump into a game of classic Mario Party with a group and personally experience what made all those frustrations fun and why the balance of control and lack of it can make unfairness an enjoyable event.

Stray Notes

- Luigi is a jerk.