Today’s post is a combination of two things I’ve been wanting to talk for some time: Celeste and narrative.

The first should be an understandable desire. Since its release a couple weeks ago, the indie title Celeste has garnered significant attention given particularly the level of difficulty its challenges involve and the way it gradually presents the player with more to accomplish. It’s the sort of game that hit me the same way Cuphead did months ago: a game that is tough to complete, but given its excellence in level design it leaves me wanting more and I find myself taking on challenges I never imagined I would even be capable of doing. More importantly, it’s a game that in both theme and design encourages persistence and overcoming of one’s limits, but more on that in a bit.

As for narrative, my main desire to speak of it stems from the fact that it’s something nearly every game provides, and yet it often feels disjointed. Too many games out there are stuck on the formula of cut-scenes telling a story that gameplay doesn’t, Which is particularly jarring when you have games featuring lofty stories of overcoming trauma, of furthering global peace, and such things, only to have those limited to cut-scenes and optional lore pick-ups while the game itself treats the main character like a one-person army. The Tomb Raider reboots in particular bothered me when it came to this.

But while it’s fun and cathartic to talk about all these instances to critique, it’s more fun and rewarding to me to talk about instances where a game knocks it out of the park. So, where the instinct initially is to talk about Celeste’s excellent game design, or phenomenal art direction and music, instead I feel like using it as an example of how it properly inserts story into a story-less design.

The Mountain

The basic premise of Celeste, since its first iteration as a game jam project, is the climbing of the eponymous mountain. All platforming challenges that follow derive from this, and advancement in the game is framed as making it higher onto this mountain, the natural conclusion of which is the summit.

For all intents and purposes, the game did not need to provide more. Ultimately, “climbing a mountain” is just as valuable as “save the princess”. It’s just a story excuse for pitting the player against challenges while providing a vacuous “why” as to how any of it matters. Vacuous, of course, in the sense that after thirty years of Mario the world has been trained to not care about “save the princess” and has instead just accepted that we do things because that’s what we do in games.

What Celeste provides though, instead of leaving the setting as the premise, is the character Madeline and the host of burdens that she brings to life in the game. Not just in cut-scenes, mind you: what the character Madeline brings to the story is literally interspersed through the levels, and her struggles justify platforming situations that are increasingly more fun, more rewarding, and more immersive.

Take Celestial Resort, the third chapter, as an example. The entirety of this chapter revolves around Madeline in an eerie hotel, dealing with the pushy owner– Mr. Oshiro– who is aggressive in wanting to retain guests and ensure the success of the hotel. Beginning on the outside, the action quickly moves indoors with a tutorial segment in which the mechanics of the level are established: dark blobs of negativity that kill instantly, keys to unlock progression, and platforms that descend under Madeline’s weight. In between rooms, the player slowly gets introduced to the rueful state of the hotel and the particularities of Oshiro’s character.

When the next segment of the level starts, the focus bends towards the cluttered state of Mr. Oshiro, which in the level takes form as a labyrinth of messy books, linen and… boxes? Shelves? Whatever they are, Madeline resolves to clear up the clutter, and so the level shifts focus towards clearing sections in order to clear the debris and open up the area in order to reach the key required for progress. Of note in this area is that the initial state of the labyrinth forces the player to notice the locked door, Oshiro and the key all within the clutter, which is a nice way of letting the player know even without paying attention to dialogue what the intended goal of the segment will be.

As the level moves on to the following area, it establishes Madeline’s increased frustration through dialogue, and sets up Oshiro as the being responsible for the miasma of dark matter all over the hotel (which, personally, made me highly frustrated and annoyed at the character myself.) When this section ends, Madeline’s darker self finally lashes out and the foreshadowed meltdown of Oshiro is represented in-game by a sequence of screens of Oshiro rushing at you while you complete platforming challenges. The stage then finally concludes with Oshiro retreating back into himself and Madeline escaping the situation.

In the context of the chapter, segments between platforming present a story about an unbalanced character, while the platforming challenges themselves establish that same sense of clutter and danger. The final segment functions both as a final gauntlet to test the lessons of the chapter’s mechanics and as a logical conclusion to Madeline’s interaction with an unstable individual outside her reach. The ultimate goal being that once complete, the player is just as glad to leave the hotel as Madeline.

It’s elegant narrative in that the entire notion of personal limitations and how we overcome them fits extremely well with the basic design concept of Celeste as a game focused on platforming precision. Madeline’s success in overcoming her darker self is also the player’s success in overcoming the challenges of the game, and as a result the conclusion of each chapter brings closure and development not just to the main character but also to the player.

Dialogue and Moments of Rest

Just as important to this sense of closure is the fact the game furthers character development through its instances of rest. I’ll gush about level design here for a bit.

Within each level, the progression of rooms is nicely organized so that new mechanics are shown and quickly tested, each time with less and less forgiving situations manufactured by either increasing the length of time that the precision needs to be sustained or the complexity of the task that needs to be done. At a particular transition in the level, an extra stressor is introduced during the emotional climax, and thereby players have to perform things they have shown themselves capable of doing while also circumventing obstacles that exist with their own particular rhythm or lack thereof.

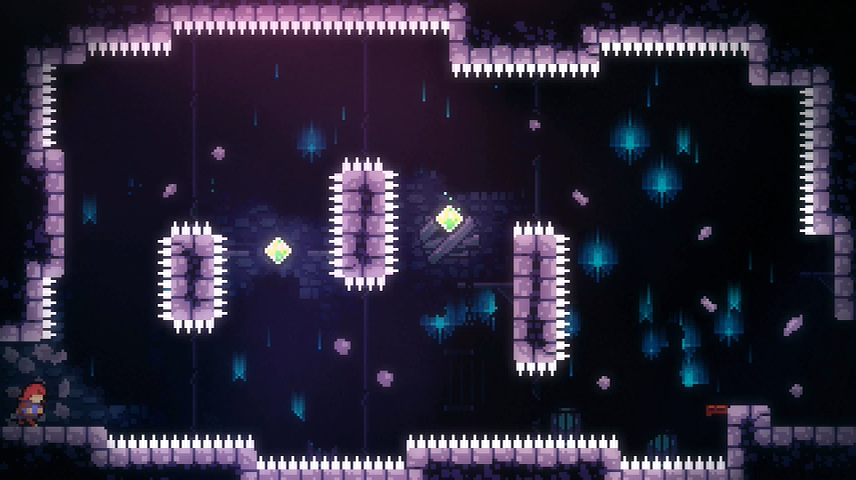

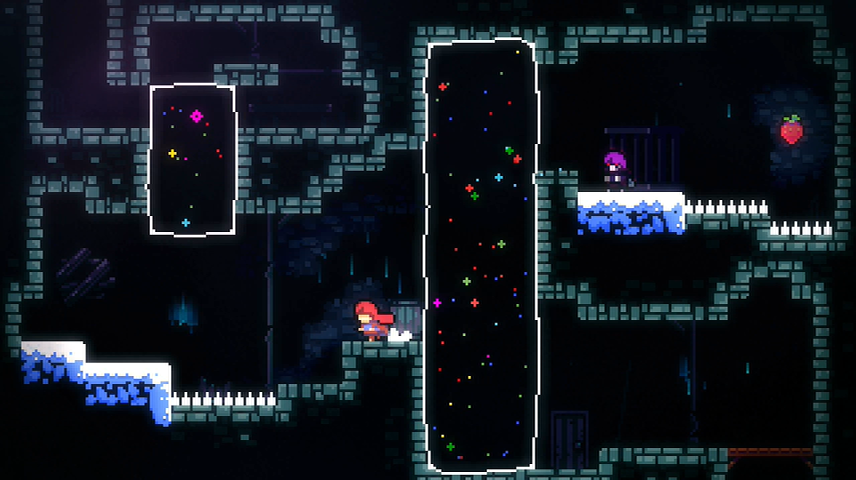

For example, the second chapter, Old Site, begins with simple platforming before introducing the mechanic of dashing through Dream Blocks. This is tested through gameplay, and then the game introduces other mechanics such as hitting key points to force a locked block to move. As the chapter reaches narrative intensity, the stressor of “Badeline” (a cool, purple representation of Madeline’s darkness) is added. In this chapter, she follows the player’s movements and kills upon touching, which forces speed and attention to movement from the player. In terms of learning, this last push reinforces the fact that the player learned and improved, as it forces players away from overthinking and into the realm of instinct and reaction.

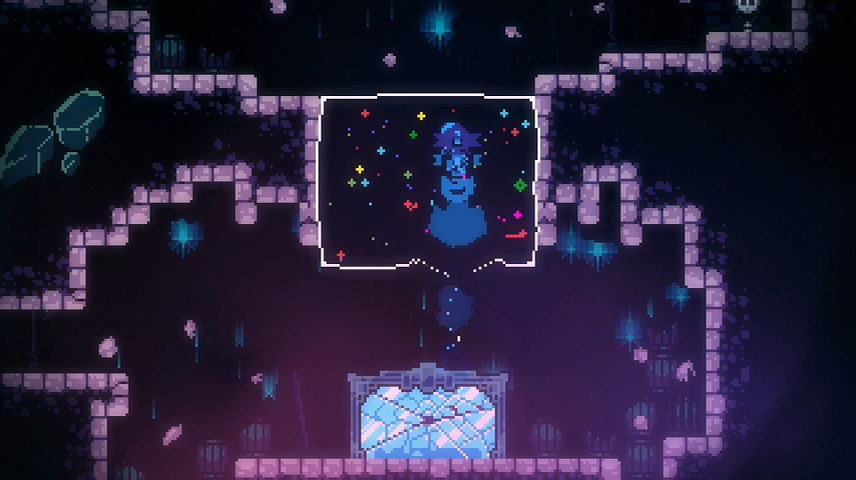

In any case, to bring this whole thing back to narrative, what is important to this sense of pacing is that between all this the developers interspersed frequent breaks: Moments during which it is possible for the player to put the game down and contemplate. Of course, there’s the obvious breaks between chapters, where the game resolves the events of the chapter with an image and (much calmer) music and pushes the player out into the stage select. But within levels too there are clear moments and sections where there are no threats, no pressure, and, usually, conversation with other characters. And oftentimes, it’s conversations with these characters that introduce intensity to the final stressor of each chapter.

This is admittedly where the game defaults into gaming tradition, wherein cut-scenes are interspersed within the game to break up segments of gaming into consumable chunks. That said, I still wish to talk for a bit about why these bits made the game better for me through their writing. Since I’m entering the realm of why I personally liked the story and what I personally liked about it, let me first get out of the way two design bits I enjoyed in these segments.

First is that these segments are completely optional at all times. This is a freebie, but it’s surprising how to this day many developers still don’t just simply allow players agency in regards to how much story they WANT to partake in. The notion of agency leads into the other bit I liked about it, that being the inclusion of moments with choice and participation. In one of the conversation segments the player is able to choose between multiple questions a character could ask, each question leading to different sides of the conversation. It was a nice instance of simulated conversation and I enjoyed the freedom to choose where things went. Of course, it’s nowhere to the level of depth as something like Oxenfree, a game with robust conversation mechanics, but I appreciated its inclusion nonetheless.

Mental Health Representation in Games

Like I mentioned, here is the bit where I begin to talk more about aspects within the story that I appreciated and less about the design of the game. For those who are bothered by this sort of thing, be aware that story spoilers exist beyond this point.

During those conversations I last spoke of, we get a significant amount of insight into the burdens that these characters are bringing to the mountain. With Madeline in particular the game constantly escalates her situation, from hinting towards her having past baggage during the beginning of the game, to more outright representations of this in her dreams, during her panic attacks, and moments in-game where the stage adopts belligerent colors and hazards that symbolize self-hate.

What I find particularly admirable about this story arc is that it begins with intent to hide this sort of personal struggle, and over the course of the story we realize it’s something that Madeline wants to dismiss and admits to hiding. Much of the resolution of Madeline’s character becomes about overcoming her issues through talking. While it’s a complicated topic to approach, given that multiple people experience anxiety and depression in different ways, the game does a good job simulating the process of overcoming it, and within the writing the game works towards normalizing mental health issues and overcoming their demonization. The end of chapter 5 and the entirety of chapter 6 (aptly named Reflection) are excellent moments of character development in resolving Madeline’s struggle, with my particular favorite moment being the conversation with Theo. Despite being a passive character, he helps Madeline significantly just in the act of accepting her and believing her (something the game hints wasn’t the case with a past relationship of Madeline’s). Their conversation is written in a way that feels very real and personal, and the game even allows for a sweet conclusion to this moment if the player follows the entirety of the dialogue options.

Within all of this is another moment I wish to call attention to, that being Theo’s grandfather’s coping mechanism for anxiety: Imagining a feather and keeping it afloat through breathing. While I have no personal experience with regards to the efficacy of this method, I do like how the game toyed with this notion. I appreciated that it wasn’t only a throwaway moment where Theo teaches the trick to Madeline and she gets better, but that the game actually simulates the exercise, and the player’s performance in this mini-game eases the tension of the scene. Even more enjoyable is the illusion being torn during an emotional climax of the game in a later chapter.

These are simple things, and this is not the first or last game to think of them, but it is worth talking about these instances as they pertain to my ultimate desire when it comes to narrative in games. Namely, that more effort and thought goes into pursuing narratives that can ONLY exist as games, instead of the path many blockbuster titles seem to take of telling movie narratives with interactive segments.

Which is ultimately why it’s fun to talk about this with Celeste in particular, a game that did not need story to sell a particular narrative. Many out there, myself included, have already experienced the overarching narrative of Celeste: the struggle of completing something genuinely difficult. Something that you have to be persistent at in order to succeed, and where many times failure is the result of one having to fight one’s own hesitation or stubbornness. With Madeline or not, this is what we still would have experienced.

But by making the effort to include Madeline’s story, of connecting her personal struggle and desire to accomplish something (anything), not only did it allow them to frame progression and chapters in a satisfyingly organic way that is more easily consumed, but it also grants the game greater weight by connecting the player more robustly with the events of the game. And it’s personally exciting for me to wonder how many young or aimless players out there will resonate particularly strong with Madeline, perhaps even naming the character after themselves, and as a result developing an experience they could not have possibly had through other media.